10/40/70: Ali: Fear Eats the Soul

This is a brief example of the 10/40/70 method of film interpretation (following the one employed by Nicholas Rombes in his book of the same title). It was written for my students in my Thought and Image course in the Fall of 2014.

Ranier Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1973) is a film of stairs and stares. Stares, because the entire film is made up of a series of looks: gazes that objectify, and trap, both the-one-being-looked-at and the one looking. These gazes are of such duration that they disturb and implicate the audience watching the film. Stairs, because we often see characters filmed behind staircases—or behind screens, railings, and staircases, simultaneously—often while being looked at, amplifying the objectification and policing of the characters. These framing devices draw attention to the ways in which the characters are trapped by their social structures (particularly of race, gender, and class) and how that stratification is perpetuated by ordinary, everyday, people, in such seemingly innocuous ways as speaking about and seeing. Emmi (Brigitte Mira) and Ali (El Hedi Ben Salem) meet by chance in a local bar. Their simple kindness to each other, and their need for each other are perfectly captured in Todd Haynes’ descriptions: “direct tenderness,” “human fragility.”

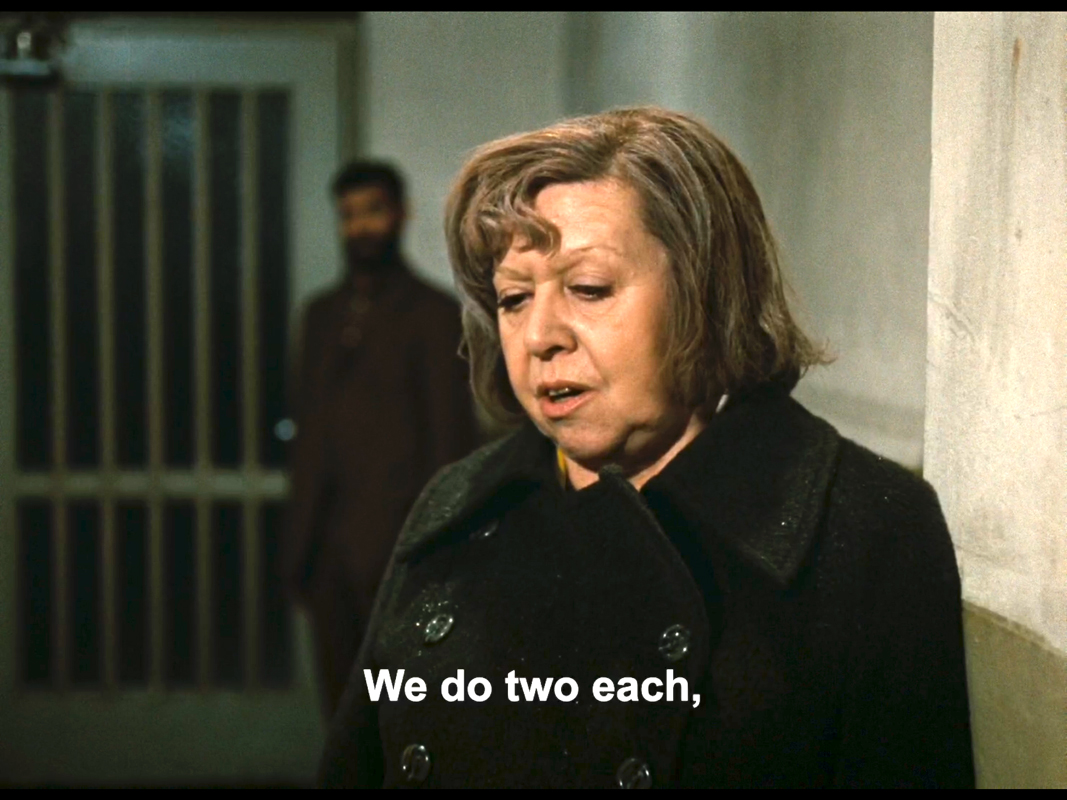

This relationship is all the more tender and vulnerable because of the age difference between them, and Ali’s status as an immigrant from Morocco. He graciously offers to walk her home, telling her in his broken German: “I go home with you to door. Not going alone, better.” In this scene, Emmi has invited Ali into the entryway of her apartment building to wait out the rain. It is the first time we learn about Emmi’s class position. Ali asks her what she does for work. “I don’t like to say. People always give you such a funny look,” she says. Ali replies, “me not look funny.” Emmi responds, “No, not you. I’m a cleaning lady.” Ali asks if it’s a big company, Emmi says that it is a medium company, but there’s a lot of glass and “it’s hard work.” “There are four of us to clean eight floors. We do two each, one in the morning, one in the evening.”

The scene shows Emmi’s awareness that others judge her due to her class position, as well as her sensitivity to that judgment (i.e. she is vulnerable to those judgments because, as a human being, she internalizes them). The blocking in this scene is straight out of Douglas Sirk. Emmi is purposely shown in relation to Ali, who remains visible behind her left shoulder, but blurred in the background, throughout the time that Emmi is speaking. When Ali is speaking, directed by Emmi’s turning to speak to him—all of this while we are still within the scene—the camera focuses in on him, Emmi remains in the foreground, her figure blurred. Writing about Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows, Fassbinder says: “Douglas Sirk’s fims are descriptive films. Very few close-ups. Even in shot/countershot sequences, the partner is always partly visible in the frame” (“Imitation of Life,” 80).

These framing devices are purposely used to show how the characters—and, by extension, the film viewer—are socially constructed. We can contrast this scene with the first scene between Ron and Cary in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows: “A traveling shot past the two of them, and in the background stands Rock Hudson, as an extra would stand there in a Hollywood film. And because the friend can’t stay for a cup of coffee with Jane, Jane has coffee with the extra. Even now all the close-ups are of Jane. Rock still doesn’t have any real significance. When he does, there are also close-ups of him. That’s so simple and beautiful. And everybody gets the point” (“Imitation of Life,” 79-80). The bars on the windowed portion of the door (framed to the left of Emmi and Ali in this scene) give a sense of foreboding to the next scene, in which the aforementioned stairs and stares both figure prominently (as forms of enclosure). These framing devices are necessary to show the ways in which the characters are not only turned into subjects by their society, but how they (and ordinary, everyday people) perpetuate and participate in that subjection (i.e. turn themselves and each other into subjects of race, class, gender, etc,). This choice of framing is deliberate because it matches the critique of the subject at work in both Fassbinder and Sirk.

This scene takes place right after Ali and Emmi are married. It is notable for the framing devices used to indicate class, social exclusion, and "looking"—the use of an objectivizing gaze throughout the scenes inside the restaurant—and because it so clearly shows Emmi's complicity with her own oppression. This complicity is expressed in her desire to eat at "Hitler's favorite restaurant" on her wedding day with her Moroccan husband. Later on in the scene, we learn that Emmi, even at her age, has never eaten in a restaurant where she has to order meat cooked as either "rare" or "medium." She doesn't know the difference between the two. This is a further marker of her class position. The shots of Ali and Emmi inside the restaurant are extremely isolated: framed through doorways in long shots and long takes, uncomfortably lingering on their social isolation as the waiter simply stares at them. Yet Emmi's complicity in her own oppression is just as important to this scene.

As Todd Haynes says about these scenes, and Emmi's naive desire to go to the Hitler restaurant, "These contradictions show us that ... even though she has these very innate, good and moral instincts, that she is also completely a subject and a construct of her society. And those contradictions are things that we can learn from, and that we can see around" (Direct Tenderness). Emmi's complicity is not shown so that the viewer can feel superior to her, or stand in judgment of her (even further turning her into a subject), but rather to enable us to pause and reflect on the ways we, too, participate in our own oppression; the ways in which we, too, are constructed by our society, the ways in which we, too, are subjects.

In this memorable scene, Ali asks Emmi to make cous cous for dinner. The denial of this request, we later learn, has serious consequences for their relationship. Emmi responds to this request with the kind of racialized, xenophobia we’ve come to expect from her working class son-in-law or her co-workers. Other than the many excuses she has previously made for the overt “soft” racism engaged in by others in her social milieu (often at Ali’s expense), this is the first time we see Emmi participate in explicitly racialized and nationalized discourses. “I can’t make cous cous,” she admonishes him, “you know that. You should get used to the way things are done in Germany. People in Germany don’t eat cous cous.” Immediately preceding this scene we witness, first, Emmi’s racist neighbors and, then, her son (who had previously disowned her due to her marriage to Ali) come to her asking her for help: despite their disapproval of her marriage to Ali, and the racism and contempt they’ve previously shown for her, despite cutting her off completely, they still need her.

Throughout the film, Fassbinder shows us how power works in modern societies: by getting people to internalize exterior relations of power, identify with those relations and, ultimately, become the bearers of them. Fassbinder shows us how the working class’ racialized resentment (of immigrants, of “others,” of Blacks and Arabs) functions as a means of “governing” them through separation. These scenes show the ease with which ordinary, everyday, people participate in their own destruction, unknowingly giving the powers that be exactly what they want. This is the overarching social structure exposed in the film. The framing of the scene is notable because we see the distance between Emmi and Ali, both spatially and through their body language. Ali is framed through the doorway—doorways are often used in the film to indicate separation, distance, division, and exclusion. Emmi, throughout the scene, is looking down. Ali’s body language indicates his exhaustion with the fact that Emmi has begun reintegrating into the community at his expense: leaving him behind and increasingly alone to bear the brunt of the racism they both had been experiencing.

I think the most important scene in the film takes place at the 60 minute mark. Emmi and Ali are sitting, alone, in an outdoor cafe. The tables are bright yellow. A happy color. The couple are alone in this large outdoor cafe, the only patrons, while the entire staff of the cafe stands in the distance and stares at them. Emmi breaks down and says that she can no longer bear the hatred: meaning the racism that is directed at her and Ali (and which Ali has had to bear alone before the relationship). This scene at the 70 minute mark, therefore, has to be read in relation to this previous scene, which marks an important division within the film: marking the point after which there is a fundamental change or transformation. The couple goes on holiday after the cafe scene (we only see them returning). After they return, most of what we are shown involves Emmi’s reintegration into her racially stratified social milieu (often at Ali’s expense). This is allowed to happen because people want something from her (but not from Ali). They need her. But they don’t need Ali, except, perhaps as an exotic “good looking set of muscles” (to quote from Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows). Emmi becomes an “insider” again as opposed to the “outsider” she became as a result of her marriage to Ali.

Sirk has made films, films with blood, with tears, with violence, hate, films with death and films with life. Sirk has said you can’t make films about something, you can only make films with something, with people, with light, with flowers, with mirrors, with blood, with all these crazy things that make it worthwhile . . . And Sirk has made the most tender ones I know, films by a man who loves human beings and doesn’t despise them as we do (“Imitation of Life,” 77).

To despise human beings is to turn them into subjects (of hate, of truth, of knowledge, of gender, of race, of sex, of class, etc.). The tenderness of Sirk’s films, and the vulnerability of his characters, are directly linked to these films’ trenchant critique of the social processes through which the subject is made. It’s not at all surprising, then, that both Fassbinder and Haynes would take up this form—the form of the melodrama crossed with noir and the women’s picture—in their explorations of contemporary experience.